By Catherine de Cates

In this blog, Global Health Fellow Catherine de Cates reflects on a field trip to Malawi to assess an innovative bone conduction hearing device that could change the lives of children with hearing loss. She describes the practical challenges and potential solutions to implement this device in the country.

Catherine de Cates, a 2023 East of England Global Health Fellow and ENT trainee registrar, shares her experience of evaluating an innovative bone-conduction hearing device in Malawi that could transform the lives of children with hearing loss. The week-long trip was part of a wider project to address childhood deafness in Malawi and allow more children with hearing loss to access education and continue learning.

Catherine’s visit involved both technical and qualitative assessments and – as she explains in the blog – was both medically insightful and deeply moving, highlighting the immense potential of this solution. You can support the project here.

“Medical devices are indispensable tools for quality healthcare delivery, but their selection and appropriate use pose a significant challenge in many parts of the world.”[1]

World Health Organization (WHO)

The Malawi backdrop

Malawi is nicknamed “The Warm Heart of Africa”, but the heart of the country lies in its rural areas, where 81% of its 21 million population reside, nearly half of whom are children [2].

Malawi struggles with an underdeveloped infrastructure and volatile economy. It’s one of the poorest countries in the world with 51.5% of the population living below the poverty line and 70% living on less than $2.15 a day [2,3]. There are only two ENT surgeons in the country, and the first audiologists were only trained in 2016 [4]. This is particularly concerning, considering there is a high burden of middle ear disease and preventable hearing impairment in children in rural Malawi [5].

Catherine, with project leads Isobel Fitzgerald O’Connor and Tamsin Holland-Brown, at a school for the deaf in Blantyre.

A call for affordable hearing devices

The World Health Organization (WHO) states that medical devices are crucial for quality healthcare delivery[6]. However, selecting and using them appropriately is no easy feat, especially in low-income environments. There are often not only cost considerations which prevent the use of solutions developed in other nations – but also regulatory, cultural, and practical barriers that make adoption difficult.

To understand how we could overcome these challenges, community paediatrician Tamsin Holland-Brown, ENT consultant Isobel Fitzgerald-O’Connor and I flew to Blantyre to conduct qualitative and practical research to understand the challenges faced in Malawi and assess potential solutions. This week-long trip included a programme of interviews with an audiologist and teachers, as well as a series of practical tests with solar chargers.

One of our first findings was when we interviewed an audiologist (one of only a handful in Malawi) at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in Blantyre, to gather more information about the situation with conventional hearing aids in Malawi. We discovered that it costs between US$100-300 to issue a hearing aid in Malawi, which is prohibitive for the majority of the population. In a school for the deaf they reported a hearing aid shortage with only 10% of the children having access to them.

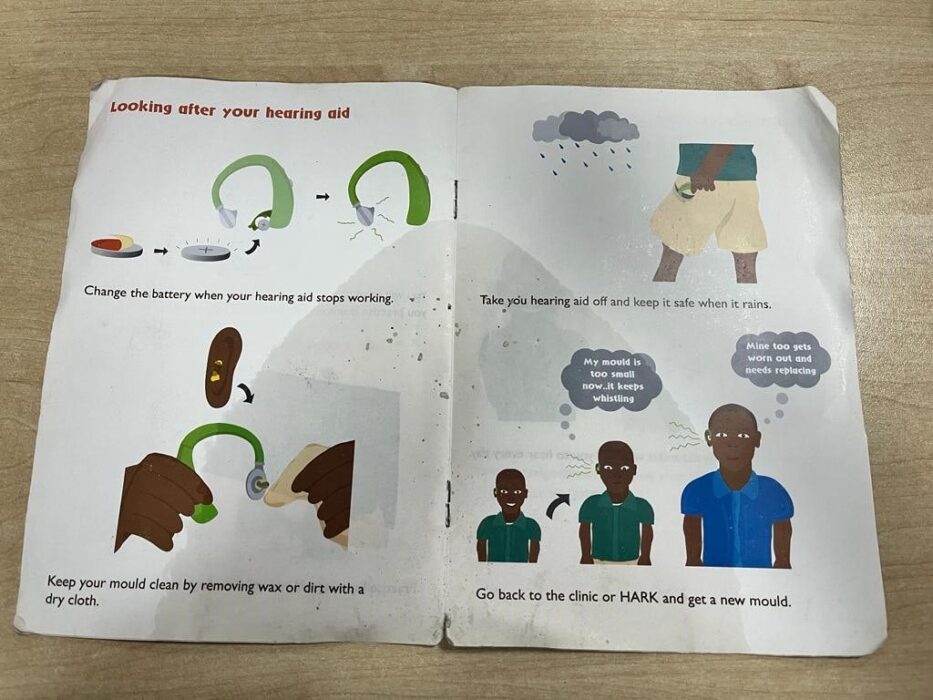

Even when hearing aids are donated free, another problem is access to batteries (which may need replacement every two weeks), and new ear moulds, further complicating access for rural populations. The travel to clinics is costly and completely unaffordable for some Malawians.

Donated hearing aids in one audiology clinic. They are unused due to the lack of hearing aid moulds, tubing and batteries.

Instructions given to patients on how to use and care for their hearing aid.

Interviewing one of the first ever audiologists in Malawi, Mwanaisha Phiri.

The bone conduction hearing device

In addition to discussing the challenges faced with traditional hearing aids, we wanted to assess a new innovative bone conduction hearing device, developed and modified by Tamsin in Cambridge for children with glue ear. This device was developed during the Covid pandemic when children were unable to access normal ENT services, necessitating a temporary solution to allow them to hear, as missing out on learning at a young age has long-term repercussions [7]. This device has a transducer which takes sound and turns it into vibration and these vibrations travel through the bone just in front of the ear. This helps to transmit sound to the inner ear within the skull. The hearing device connects via Bluetooth to a microphone which is worn by the person speaking, for example a teacher. The bone-conducting hearing device we tested offers a simple, cheap, and chargeable solution, which could make it an ideal option for children in rural, low-income settings. The aid can also be worn by those with discharging ears for whom conventional hearing aids are contraindicated. This is an important consideration in a country with so few ENT surgeons.

With all these things considered we thought this device may be suitable for low-resource environments like Malawi, so we set about looking at this in more detail.

The bone conduction hearing product is made by Raspberry Pi, a UK-based charity who help young people realise their full potential through the power of computing and digital technologies, and has been adapted for wear by children.

The headset, microphone and mobile app which together are designed to help children learn.

During our trip to Blantyre, we visited the audiology department at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital and Maryview School for the Deaf. We found that the bone conduction hearing device was very well received, with a large study almost underway to test it on school-aged children. Local staff also provided positive feedback on the feasibility of the device and some practical suggestions. The hearing device seemed completely transformative for those who used it. For example, one child at the Maryview School for the Deaf was dancing to music and signing the words of the song played through the headset to his classmates. Another girl with longstanding ear disease and infections was given the headset at age 13, and now aged 16, had been using this headset with the microphone to support her hearing at school (in a class of 86). The headset (worn by the child) paired to the remote microphone (worn by the teacher) had provided clear access to the teacher’s voice. Having been unable to pass end-of-year exams previously, she had passed school exams every year since using the device. She now has ambitions to study medicine. She also used the device for socialising with friends and in the family home.

This boy at Maryview School for the Deaf could hear his teacher through the hearing device and microphone. In this photo he was told put his hands in the air. We were pleasantly surprised to see the benefit gained by some children at this school who were generally at the more severe end of hearing impairment.

We saw the incredible impact this easy to administer solution could have on the quality of life of those who used it. The bone conduction headset is visible and much more noticeable than a conventional hearing aid. We looked at potential stigma surrounding the device but found it to be very well received by the Malawians that we spoke to.

Not only is it more affordable than traditional hearing aids (currently £25), it also requires less intervention from healthcare professionals. The rechargeable device eliminates the need for batteries. However, considering that only 6.6% of the rural population has access to electricity, alternative charging methods are essential.

After daily use for three years in the classroom, to socialise outside and using the device at home to hear her mother, this 16 year old girl’s device had taken some knocks but was still working (pictured above, right). A friend had trodden on her bag at school and the headset had become damaged, but they repaired it with tape and it was still working. The child had not seen a healthcare professional for three years but managed to hear and access education in that time.

Harnessing the power of the sun

Solar charging emerged as a promising solution to power these bone conduction hearing devices in Malawi. Many people in the country already rely on solar charging to light their homes. Additionally, Malawi is investing in solar energy projects like the 20-megawatt Golomoti Solar Project [8].

Our research focused on the practical assessment of solar charging options and qualitative interviews with the audiologist Mwanaisha and teachers in the school. Electricity seems to be expensive and difficult to access in rural communities. We found people using solar panels in rural markets and solar chargers in homes, mostly for lighting. Local people in Blantyre also expressed positive opinions on solar energy use in Malawi.

During the rainy season, there may be limited sunlight for solar charging, so the device may need a battery pack with backup energy storage for those days with insufficient sun.

A promising future

Our trip validated not only the challenges facing Malawi as it deals with hearing loss, but also that the bone conduction hearing device has the potential to significantly improve the quality of life for children with hearing loss in Malawi. Its affordability, reduced need for healthcare professional intervention, use in discharging ears and compatibility with solar charging make it a promising solution. Not only this but by building clinical research relationships in the region we can address the challenges and embrace innovative solutions, so create a brighter future for these children and their families.

You can support this project via the JustGiving page.

References

1. World Health Organization. Prioritizing medical devices [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Apr 24]. Available from: https://www.who.int/activities/prioritizing-medical-devices

2. US government. The World Fact Book: Malawi [Internet]. cia.gov. 2023. Available from: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/malawi/

3. The World Bank. The World Bank Data. 2023; Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/country/malawi

4. Mulwafu W, Prescott C, Fagan J. Addressing ear and hearing care through task sharing: the Malawian experience. ENT Audiol NEWS [Internet]. 2020; Available from: https://www.entandaudiologynews.com/features/ent-features/post/addressing-ear-and-hearing-care-through-task-sharing-the-malawian-experience

5. Hunt L, Mulwafu W, Knott V, Ndamala CB, Naunje AW, Dewhurst S, et al. Prevalence of paediatric chronic suppurative otitis media and hearing impairment in rural Malawi: A cross-sectional survey. Brennan-Jones C, editor. PLoS One [Internet]. 2017;12:e0188950. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188950

6. WHO. Priority Assistive Products List. GATE Initiat [Internet]. 2016;1–16. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/priority-assistive-products-list

7. Holland Brown TM, Fitzgerald O’Connor I, Bewick J, Morley C. Bone conduction hearing kit for children with glue ear. BMJ Innov [Internet]. 2021;7:600–3. Available from: https://innovations.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjinnov-2021-000676

8. InfraCo Africa. Golomoti Solar [Internet]. [cited 2023 Apr 24]. Available from: https://infracoafrica.com/project/golomoti-solar/

Special thanks to:

– Mwanaisha Phiri, Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, Blantyre

– Maryview School for the Deaf, Malawi

– Lovemore Mzati Nkhalamba and Thomas Hampton, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine

Return to blogs