By Evan Edmond

In this blog, East of England Global Health Fellow Evan Edmond reflects on his fellowship year and the learning he’ll takeaway from it. As part of his fellowship, Evan spent time in South Africa and South India, where he witnessed both the commonalities in neurological syndromes as well as the importance of communication, cultural awareness and compassion in providing the best care for patients.

“I’m writing this from the Greater Anglia train from Whittlesford Parkway to Tottenham Hale. It’s a crisp February morning, with frost covering the countryside like icing sugar and a blanket of low-lying mist. The rising sun is an orange disc cutting through the mist, casting an orange glow through leafless trees over the monochrome fields.

It’s very different from my Cape Town commute in South Africa. There too, the sun would be rising over the Green Point stadium, followed by a sweeping bend on the elevated N2 motorway, providing panoramic Table Mountain views. The sky is a changing canvas, a blue expanse on some days, but when the wind is right, there is a flowing tablecloth of clouds over Table Mountain, with eddies of cloud roiling and melting away over the edge.

It’s also very different from my Nagercoil commute in South India, where I have one hand hovering over the horn, and scooters and auto-rickshaws could appear at any moment. Occasionally though, there is a break in the buildings, and the fierce Indian sun beats down over a field of waving green leaves of banana trees, with the rolling hills of the Western Ghats in the background, underlined and outlined by brick-red soil paths.

A commute is a commute though, and after a moment of joy, peace, and gratitude, I mentally shift gear and examine the day ahead. There is a neurology clinic, a round of ward patients, and then I will sit down to catch up on admin, and try to fit in a sliver of research time. Neurology is neurology – whether in southern England, South Africa, or south India. In typical neurology fashion, I will reflect on the global health fellowship experience using a series of neurological cases.

South Africa

Arriving at Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town is an experience in itself. From the entrance junction teeming with minibus taxis I ascended to the main entrance, with the historic Cape Dutch outpatient building on the right, and the enormous modern monolithic hospital block on the left.

We meet the first patient in the Neuroscience Institute. She is a volunteer in the Ingqondo study (meaning Brain in Xhosa) of brain ageing in the South African context. She is dropped off along with her sister by a taxi. T, the study research assistant warmly greets her in Xhosa, along with handing her a meal and a drink. She lives in a peri-urban township, and it has already been a 90 minute long trip for her. She is immaculately dressed. Later, in the memory clinic, she tells the team that she has had some memory difficulties, and her sister notes that she will often repetitively take down and re-arrange the objects from shelves in their house.

She has cognitive testing performed by a neuropsychologist showing lower scores on memory and verbal fluency. Standard memory clinic so far. The nuance appears when a social history is taken, with prompting in Xhosa by Z, another research assistant. This includes leaving school after primary school in the apartheid era, precisely identifying the dwelling types she has lived in (ranging from corrugated metal shacks to her sister’s brick house), history of alcohol excess, head injuries, interpersonal violence, psychological distress after the loss of her son, and so on. While a good social history is critical in any memory clinic, the unflinching comprehensiveness of the South African social history is a cut above what I have seen in the UK.

For the cognitive tests, it is critical to calibrate the expected performance in relation to this. One test involves identifying pictures of animals. Our participant cannot identify a picture of a rhino. The team fills me in that despite being South African, given her education and social background she may never have learnt the word for rhino in school, or seen a picture of one.

This single patient crystallised for me the huge challenge involved in the research project I was collaborating on. I was investigating computerised cognitive testing data in South African people with HIV from a previous study in a similar social context, and reviewing the meticulous processes needed to gather detailed socioeconomic, education, drug, alcohol, head injury, mental health data, and then model the impact of these various interacting factors on cognitive test performance.

In presenting my data to the research group at the neuroscience institute, and visiting the community clinic in Gugulethu where patients were recruited, the juxtaposition of severe socioeconomic disadvantage with new ambitious work in neuroscience stood out. The vast majority of study participants now own a smartphone – raising the prospect of broad based cognitive screening for early identification of cognitive low performance. However, if you identify it, what can you actually do about it? In general, social care and support are very good through family and local informal carer networks, however medications such as donepezil are not considered sufficiently cost-effective to be government funded. Every research conversation in statistics or analysis is followed by one of real-world application, which I found inspiring to be part of. We have now written up our work on applying computerised cognitive testing to detect early cognitive changes in the South African setting, and I hope to continue to work in this field going forward.

While in Cape Town, I was fortunate to also experience the study planning meetings for the group, as well as neurology registrar teaching on HIV neurology shared with the team in Lusaka, Zambia. I attended formal neurology ward rounds on the clinical side too, which is where we meet the next patient.

She has weakness in her left leg. When she walks it drags behind her. It has caused her significant anxiety. When she is examined by the consultant neurologist, the left leg cannot push at all against resistance. When he distracts her focus to the other leg, a test called Hoover’s test, as if by magic, the power returns to her left leg. He explains this as a “functional” weakness, and reassures her that she can improve with physiotherapy. He takes the time to ask what is happening in her family life, and will refer her to a psychiatrist to manage her mental health. She will walk out of the hospital. She has been unable to work or look after her children. Having the diagnosis and treatment plan are likely to help mitigate the stresses that led to this condition developing.

In England, neurology registrars often complain about seeing patients with functional problems – it can be a very difficult conversation with a patient who has been dismissed by others. The patient must implicitly trust your clinical assessment as there is no simple investigation to make the diagnosis. The patient has to see with their own eyes the clinical sign you are demonstrating, and really understand that they can indeed move. The explanation has to be compassionate, and gently handle possibly severe adverse life experiences. In summary, patients like this need high-level neurology clinical skills allied with high-level communication skills and compassion. No matter which country you are in, it is a pleasure to see a master at work in handling a case like this well.

The impact of any biological disease on health is transformed through a long sequence of filters….When healthcare workers grow up and train in a particular place, those filters can fade into the background and be taken for granted. I found that by spending time in healthcare in South Africa and India – or even when comparing London and Norwich in England – that the accumulation of differences generated by these filters became obvious.

South India

We move north-east several thousand miles for our next patient. It is a month later, and I am opportunistically shadowing a neurologist for the last few days of a visit to my family in southernmost India. We see a young boy who has come into hospital after a generalised seizure. He did not have any concurrent illness. It is possible that he may grow out of this, but he will need to be followed up in case it returns and he needs treatment. I follow the neurologist into a room with a family in a high state of anxiety. While the child has returned completely to normal, and is clambering all over the hospital bed, his mother stands at the end of the bed with furrowed brow, hands clasped, and eyes downcast. Next to her is the father, and next to them the child’s grandmother.

The neurologist goes through the scans with the family, as well as explaining what a seizure is (uncontrolled electrical brain activity). He goes on to specifically say to the mother that this was not caused by anything she had done wrong in caring for the child, or in pregnancy, and that the child is likely to live a normal life. The parents’ shoulders palpably relax on hearing this. Later he tells me that the grandmother there is the mother-in-law to the mother, and in his experience, families may mis-attribute health problems in young children to perceived errors by the mother in particular. Being aware of cultural family dynamics he had found it improved patient engagement with care and the outcome if treatment was needed to remove blame for causing the condition from the conversation as early as possible. When I bring in a patient from the waiting room to a clinic in England, I make a note of who is accompanying them, their name and relationship, to put what they say into context. I enjoyed witnessing the same process in the south Indian context too.

After returning to the clinic that afternoon the first afternoon patient came in. Within 20 seconds, after the patient had shown us that he became weak on the left side, and that his left hand and leg became clumsy, the neurologist glanced over at me – we both knew he had an ataxic hemiparesis, and therefore almost certainly a stroke in the right internal capsule. The scan was done several hours later and confirmed this. No matter what language, social setting, or location, some neurological syndromes are incredibly consistent, driven by localisation of brain anatomy and function.

What would I like you to take away from these different cases and experiences?

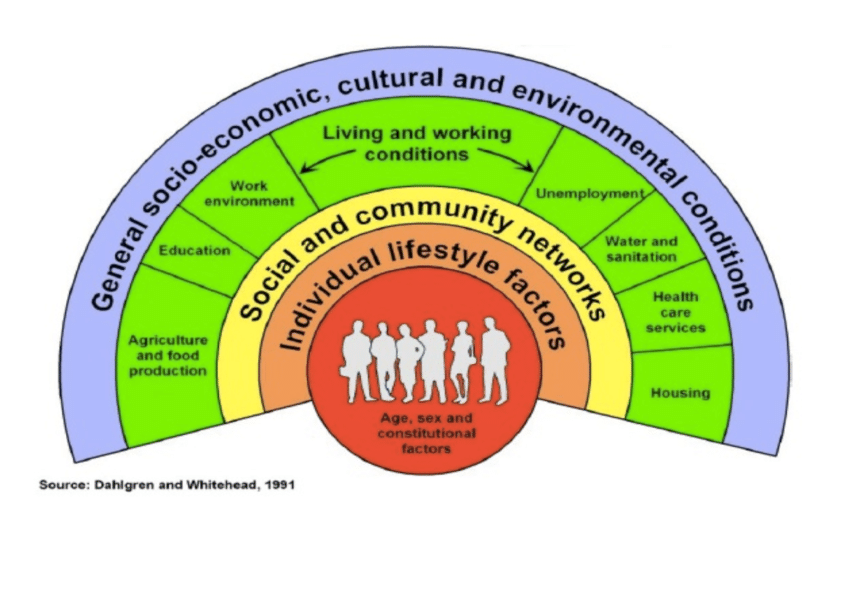

My main reflection was that the impact of any biological disease on health is transformed through a long sequence of filters, including but not limited to genetics, climate, nutrition, other illnesses, available treatments, social structure, language, psychological stressors, traumas, substance exposure, housing, wealth, and on and on. When healthcare workers grow up and train in a particular place, those filters can fade into the background and be taken for granted. I found that by spending time in healthcare in South Africa and India – or even when comparing London and Norwich in England – that the accumulation of differences generated by these filters became obvious. The resulting healthcare outcomes can vary differently. This is certainly not a new insight, and these “filters” are analogous to the colours of the rainbow in Dahlgren and Whitehead’s “Rainbow model” of social determinants of health (see above).

Seeing this phenomenon repeating itself in different places made me resolve to re-examine this in the UK, where the Marmot Review has laid out in detail how socioeconomic status influences neurological outcomes. It made me fearful for the impact of USAID cuts in slashing the services I witnessed at the Gugulethu Community Clinic – leaving no other option for those patients awaiting their blood pressure, diabetes, or HIV medications – with increased, avoidable, suffering and death now likely. It made me better understand the challenges facing international medical graduates in the UK, where a new set of filters must be studied from an unwritten curriculum.

Finally, it showed the intrinsic value of global health collaboration, where different perspectives enrich the discussion, compensate for each other’s blind spots, and find real-world treatments and solutions for the world’s major health problems.”

Find out more about the East of England Global Health Fellowship scheme or contact us at info@cghp.org.uk

Return to blogs