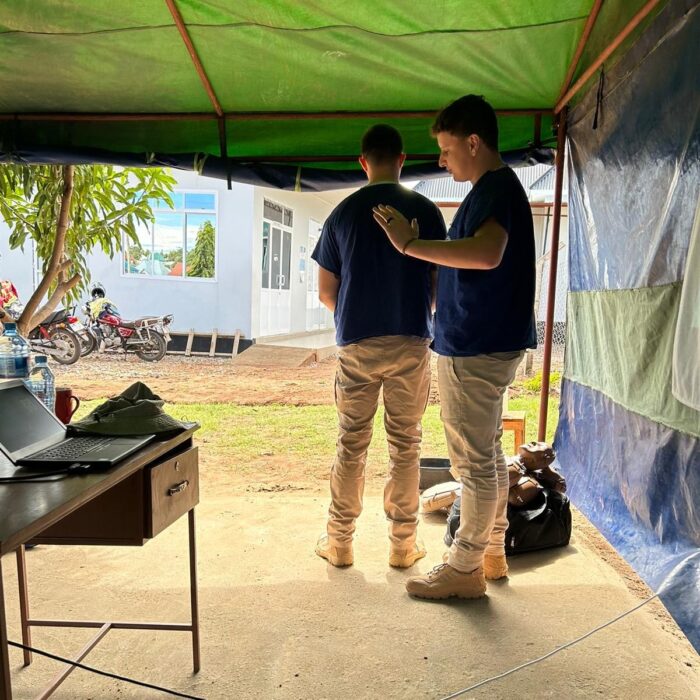

Max Burroughs, a therapy radiographer at Addenbrooke’s Hospital, used a CGHP grant to travel to Mwanza, Tanzania to help deliver training in four lifesaving areas.

CGHP’s Grant Scheme supports Cambridgeshire-based healthcare staff to undertake voluntary healthcare placements with low- and middle-income countries. Max used his grant to travel to Mwanza, Tanzania with Pre-Hospital Care & Aid Worldwide, to deliver training in four crucial areas: Basic Life Support (BLS), Manual Handling, Infection Control, and Stop the Bleed. The project focused on the specific needs and challenges of rural healthcare providers, and involved community volunteers in recognition of the vital role they play in areas where medical resources are scarce.

Here Max explains more about the project and the impact it had both on him and the local community.

“The impact of our project on the healthcare workers in Tanzania, especially in Mwanza, was profound and multifaceted. The training sessions I conducted were attended by a diverse group of healthcare providers, including doctors, nurses, community health workers, and notably, Boda Boda riders.”

What is unique about this project?

In partnership with the Rural Tanzania Health Movement, the project was uniquely tailored to address the specific challenges and needs of rural healthcare providers. This focus on rural settings is often overlooked in mainstream medical training programmes but is critical in a country like Tanzania, where rural areas face significant healthcare disparities.

The project went beyond training healthcare professionals by involving community volunteers, particularly in the “Stop the Bleed” training. This approach recognised the vital role that non-medical community members can play in emergency situations, especially in areas where medical resources are scarce.

The training was designed not just as a one-time intervention but as a sustainable knowledge transfer process, including follow-up programmes and the development of training materials. It was also carefully adapted to the local healthcare context of Mwanza, and considered the region’s specific medical challenges, cultural nuances, and resource limitations.

These unique features collectively ensured that the project had a profound and lasting impact on the healthcare landscape in Mwanza and the surrounding rural areas, empowering both medical professionals and community members with vital lifesaving skills.

Who is involved?

Pre-Hospital Care & Aid Worldwide is the primary organiser, responsible for planning and executing the mission as well as overseeing the training programmes, providing expert trainers, and managing logistical aspects.

Local healthcare facilities in Mwanza were key local partners, offering venues for training, identifying participants who would benefit most, and providing insights into local healthcare challenges and needs.

Rural Tanzania Health Movement also played a crucial role in understanding and addressing the specific healthcare needs of rural communities in Tanzania. They assisted in tailoring the training modules for rural settings and facilitate outreach to remote areas, ensuring widespread and relevant impact.

What was your role in the training?

I delivered Basic Life Support (BLS) workshops, where I taught local healthcare workers and community volunteers the fundamentals of life-saving techniques. This included CPR, using automated external defibrillators (AEDs), and managing a choking patient. My focus was on ensuring that participants could confidently provide immediate assistance in emergencies, enhancing their ability to save lives.

Recognising the high risk of injuries in patient handling, I led practical sessions on safe and efficient manual handling techniques. This training covered the correct ways to move, lift, and transport patients, aimed at minimising the risk of injury to both the healthcare provider and the patient. I emphasized ergonomics and safe practices that are vital in a healthcare setting.

For the Infection Control Education segment I focused on educating participants about critical infection control practices. This was particularly important in the context of ongoing global health challenges. I covered hand hygiene, the use of personal protective equipment (PPE), and protocols for preventing the spread of infectious diseases within healthcare environments.

I also provided hands-on training on how to quickly and effectively stop bleeding, such as applying direct pressure, using tourniquets, and wound packing. The aim was to equip non-medical community members with the skills to act effectively in the critical moments following an injury, potentially saving lives.

What impact did it have?

For the doctors, nurses, and community health workers the Basic Life Support (BLS) training was a critical update to their existing knowledge, reinforcing their ability to respond effectively in emergency situations. In Manual Handling, they learned techniques to minimize patient and self-injury, which is essential in their day-to-day work. The Infection Control training was particularly timely, equipping them with necessary practices to maintain safety during health crises like the COVID-19 pandemic.

One of the unique aspects of our project was the inclusion of Boda Boda riders (a motorcycle taxi service) in the ‘Stop the Bleed’ training. As they are often the first on the scene of road accidents, equipping them with skills to manage bleeding was crucial, potentially saving lives in their communities. Including non-traditional first responders like Boda Boda riders in our training has started a shift towards community-based health services. This approach widens the safety net for emergency care and creates a more responsive and resilient healthcare system, especially in rural and hard-to-reach areas.

The most significant takeaway for all participants was the confidence they gained in their ability to provide immediate and effective care in emergencies. The hands-on approach of the training meant that they didn’t just learn techniques theoretically but practiced them until they felt adept. This hands-on experience is invaluable in a country where medical emergencies often occur far from medical facilities, and the first response can mean the difference between life and death. A quote that encapsulates the impact of this project came from a local nurse:

“The skills we’ve learned here aren’t just procedures; they are life-saving tools. Now, when an emergency comes through our doors, we don’t just see a patient; we see a life that we’re fully equipped to save.”

Another powerful quote came from a Boda Boda rider who attended the Stop the Bleed training:

“Before this training, all I could do was wait helplessly for the ambulance in an accident. Now, I can be part of the solution; I can save lives.”

These quotes underscore the personal and professional transformation experienced by the participants, highlighting the profound impact of the project not only on their skills but also on their perspective towards patient care and emergency response.

What was the biggest difference about the Tanzanian healthcare setting?

The biggest surprise about the healthcare setting in Mwanza was the resourcefulness and resilience displayed by the healthcare workers in the face of significant resource constraints. Their ability to improvise and make the best use of available resources was remarkable and it was enlightening to see how they could deliver effective care by creatively utilising what was at hand.

The level of community involvement in healthcare was another surprising aspect. In particular, the role of Boda Boda riders in emergency response was a unique and innovative approach to pre-hospital care, which is not commonly seen in Western healthcare settings. This community-based model of care was both effective and inspiring, showcasing a strong sense of communal responsibility for healthcare.

The patient-to-healthcare worker ratio was significantly higher than what I had experienced elsewhere. The healthcare workers often had to manage many patients, which was challenging yet handled with admirable dedication and efficiency. The healthcare professionals in Mwanza were also typically trained to handle a wide variety of medical situations, much more so than in many Western countries where there is a higher level of specialisation, and this versatility was a testament to their adaptability and broad skill set.

Despite the challenges, there was a palpable enthusiasm among the healthcare workers for learning new skills and improving their practice. Their commitment to professional development, even under challenging conditions, was both surprising and deeply inspiring.

What was a particular highlight of your visit?

One of my favourite experiences was during a Basic Life Support (BLS) session. I was teaching CPR, and despite the language barrier, the enthusiasm and eagerness to learn from the participants were palpable. Their focused attention turned into excitement as they practiced on the mannequins, each trying to perfect their technique. It was a moment where the universal language of healthcare and the shared goal of saving lives transcended all barriers. This passion and dedication were both inspiring and deeply gratifying.

How will the work be sustained longer term?

To ensure long-term sustainability, we focused on building local capacity. This involved training ‘trainer candidates’ among the local healthcare workers, equipping them to teach the skills we introduced to future trainees. We provided comprehensive training materials and resources in both English and Swahili, ensuring they were accessible and relevant to the local context. Additionally, we established a follow-up programme to monitor progress and offer continued support remotely. Partnerships were formed with local healthcare facilities and community organisations to embed these skills into their regular training programmes. This approach was designed to create a self-sustaining model, where the initial training we provided would be perpetuated by local healthcare professionals, ensuring ongoing impact and relevance.

Max’s visit was made possible with funding from CGHP’s Grant Scheme. The Scheme is open to staff members from Cambridge University Hospitals and the wider Cambridgeshire healthcare community who are undertaking a voluntary healthcare placement with a low- and middle-income country either remotely or in person. Find out how you can apply.

Return to case studies